Climate Action and Decolonization: Indigenous Perspectives

This inquiry takes a deeper look at how Indigenous peoples have been and are leaders of climate action as well as how climate change is exacerbating existing socio-economic inequities and impacting some cultural practices. The following resources, guiding questions and activities aim to encourage thoughtful consideration on how climate justice is inherently connected to decolonizing processes and truth and reconciliation. We invite students to consider the depth of knowledge that exists in the diversity across Canada and work to ensure that Indigenous ways of life are not at risk in Canada’s future.

Jump to:

The rapid and profound climate changes are putting lands and territories of many Indigenous communities (Metis, Inuit and First Nations) on the front lines of mitigation and adaptation efforts. According to Terry Teegee, regional chief of the BC Assembly of First Nations, Indigenous communities are often the first to experience the impacts of climate change. Indigenous communities have a strong dependence on and close relationship to the environment and its resources. Threats to Indigenous ways of life due to the changing climate are complex and wide-reaching. Specific experiences vary considerably based on the area or region in which communities are located. One of the general impacts that climate change is having on Indigenous communities in Canada include an increased risk of physical harm associated with traditions or activities including hunting and fishing. Very experienced harvesters are being forced to alter hunting strategies and take into consideration the lack of rescue facilities available (Canadian Geographic Indigenous Atlas of Canada). Therefore many people are also experiencing a loss of food security in part due to altered animal migration patterns as well as human travel routes impacting people’s ability to access country foods. Indigenous people may be experiencing threatened sovereignty and a loss of communities and culturally significant locations due to rising sea levels, flooding, coastal erosion, and melting permafrost.

How does climate change disproportionately affect Indigenous communities?

Indigenous people in Northern communities have historically demonstrated an incredible ability to adapt to varied and changing circumstances. However, as the impacts of climate change intensify, successful adaptation becomes increasingly challenging. When considering climate change and its effect on Canadian citizens, it is imperative to acknowledge the social and cultural inequalities that exist when it comes to contribution, mitigation and adaptation. For instance, according to the Government of Nunavut, despite the small contribution made by a territory like Nunavut to national greenhouse gas emissions, the effects of the global excess are felt heavily by the citizens.

Impacts and path forward in The Arctic – Inuit Peoples

According to the IPCC (2019), the cryosphere changes in the Canadian Arctic have negatively impacted human health in several key ways. There have been dramatic increases in food and waterborne diseases, malnutrition, injury and serious mental health challenges especially among Indigenous people. Additionally, Indigenous peoples and other Arctic residents have had to change the timing of various activities in response to seasonal changes and safety of travel on ice, land and snow. Some coastal communities have planned for relocation due to failures associated with flooding and thawing permafrost. According to the IPCC, “limited funding, skills, capacity and institutional support to engage meaningfully in planning processes have challenged adaptation.” Inuit people have used and occupied Arctic and Subarctic land, ice and water for thousands of years, documenting use and reliance on the land and waters for many generations. It is imperative to recognize the critical role that Inuit people must play in developing adaptation and mitigation strategies to address the many complex challenges that define the Canadian North.

Moving Away from indigenous stereotypes (‘passive witnesses,’ media portrayal)

First Nations people have been and continue to be leaders in the fight against climate change. Inuit leaders brought warnings about the impacts of climate change to the international stage as far back as the Earth Summit in 1992. There are many groups working towards reconciliation in Canada that recognize the leadership of Indigenous cultures when it comes to sustainability as a central tenet of their relationship with the environment (Sustainable Canada Dialogues).

Due to the unique context of Indigenous rights and impacts, (governance, economy, infrastructure and activities) many wide-spread solutions that policy makers have put forward do not acknowledge that Indigenous communities are already engaged in important climate change mitigation strategies that are deeply rooted in Indigenous customs and traditional practices (ICA, 2019). In many ways, Indigenous knowledge and practices can be an incredible resource for learning strategies to adapt to climate change. It is important to think critically about the sources from which we gather information on indigenous rights. In too many instances, a biased version of an event is told and shared widely through the media; stereotyping indigenous activists and protestors, misconstruing actions and portraying a radical, negative picture to the general public.

According to the 2018 Indigenous Climate Action Report, the implications of culturally embedded perspectives are significant: National “Environmental” policies often ask relatively narrow questions about how to reduce emissions and mitigate or stall damage, whereas Indigenous water walkers, for example, are asking us, “How do we get to a spiritually grounded and more fully integrated way of life where we can swim, eat and drink from uncontaminated lakes and rivers?” There is a great deal that we can learn from the way that Indigenous peoples have lived harmoniously and sustainably with the land for thousands of years. Indigenous perspectives should be a central voice for policymakers and citizens of Canada to hear as we are adapting and developing sustainable communities of the future.

To hook student interest, choose one or more of the provocation videos to initiate engagement.

- Autumn Peltier, water advocate [Global News]: 2:29 minutes – Water advocate Autumn Peltier discusses her initiative to promote awareness about the sacredness and importance of clean drinking water.

- There’s Something in the Water directed by Ellen Page and Ian Daniel. A 2019 documentary examines environmental racism and the effect of environmental damage on Nova Scotia First Nations and the role of Indigenous women to care for water and fight to preserve this basic right.

- Eriel Deranger – Indigenous Climate Action: Community-based solutions rooted in decolonization [Climate Atlas Canada]: 3:42 minutes “Real climate solutions are rooted in a return to the land – a return to and of the land – and are rooted in decolonization,” says Eriel Deranger, Executive Director of Indigenous Climate Action (ICA)

- Melina Laboucan-Massimo – Renewables in the heart of the Tar Sands [Climate Atlas Canada]: 4:36 minutes – The Lubicon Cree Nation situated in Northern Alberta are leaders in the low-carbon energy transition. In response to the drastically changing landscape, community member Melina Laboucan-Massimo took charge of the construction of a 20KW energy system which she calls “a beacon of what is possible in our communities.”

- Adapting to Sea Level Rise: Indian Island, NB [Climate Atlas Canada]: 7:58 minutes – Indian Island First Nation Chief Ken Barlow relied on science and traditional knowledge to predict that his nation will be underwater by 2100, the community is now making a big effort to prepare and protect their homes from this inevitable outcome.

- Back the Buffalo: Lethbridge Alberta [Climate Atlas Canada]: 3:36 minutes – Dr. Leroy Little Bear of Kainai First Nation discusses the environmental change he’s witnessed over time and why buffalo restoration in Alberta is critical for restoring ecological balance.

- Meechim Project: Garden Hill First Nation [Climate Atlas Canada]: 10:59 minutes – This video is about the Garden Hill First Nation community, a place that is only accessible by air or ice roads, and their effort to build a self-sustaining farm with the goal of attaining food sovereignty.

- Climate Change in Great Bear Lake: [Produced for the Déline Renewable Resources Council in collaboration with the elders of Déline, NT] 14:47 minutes – This video looks at the ecological impacts from climate change on Great Bear Lake through the eyes of Déline NT Elders and their traditional ecological knowledge.

Critical Thinking Questions – created by Global Encounters, adapted from Let’s Talk Science – Indigenous Perspectives on Climate Change.

- What are some steps that you can take to decarbonize and decolonize? What is meant by decolonization?

- Are there measures being taken by governments or other groups that are creating a deeper impact of climate change on Indigenous populations? (i.e. Modern Colonialism: the policy or practice of acquiring full or partial political control over another country, occupying it with settlers, and exploiting it economically)?

- Compare and contrast the impact of climate change on your physical region and Indigenous groups to that of international Indigenous groups. For example, a student in BC may talk about the impact of a warming climate and the decline of salmon available for fishing.

- Identify ways that the media portrays indigenous rights. Find recent examples in the media to support your answer. Is the portrayal or description accurate?

- How can you become a climate change hero? Share a brief outline for an action plan you could take to become a climate change hero. To help create a plan, consider the following questions:

- What can I do to reduce my carbon footprint?

- What are the effects of global climate change on today’s world?

- Why is it important to preserve the First Nation area, treaty area, provincial crown land and/or Federal Crown land?

- How do we assist Indigenous groups to preserve their land?

See the full resource to view these questions in context check here.

Note: These questions would also be a rich starting point for a dialogue in the classroom as the students pursue and consolidate their learning – either by assigning students various positions to stretch their thinking or allowing their own responses to guide the dialogue.

Use one or more of the following suggestions to help students build knowledge on Indigenous perspectives on climate change.

- Invite local traditional knowledge keepers into your classroom as a guest teacher or resource person. Identify sources of traditional knowledge keepers from local First Nations, Indigenous organizations in towns and cities, government sources.

- Plan a field trip for students to learn about Indigenous traditions and cultural values, explore similar or diverse experiences of climate change, and ensure students foster cultural sensitivity and respect.

- Students should have access to quality Indigenous resources (books, websites, oral stories and classroom activities).

- Refer to the “additional resources” section below for some examples

- Search on R4R.ca and filter your search by: subject, grade, and theme: “Indigenous Knowledge”

- Another starting point for quality Indigenous teaching resources is The Deepening Knowledge Project.

We have included a list of high-quality resources for students and educators to explore (see text box below). These could be provided to students to extend learning or search for answers to any remaining questions.

Resources for Additional Research |

|

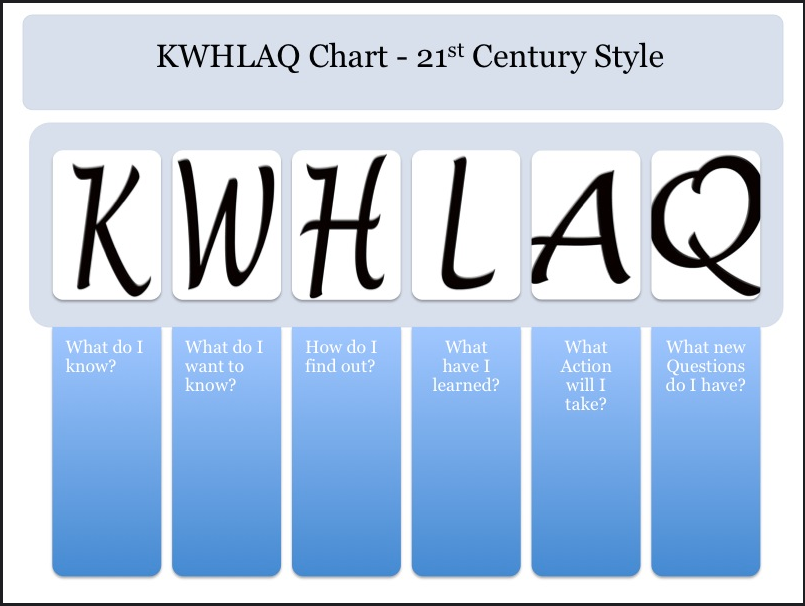

In order to determine where students are in their learning process, create a KWHLAQ Chart, which is an extended version of the KWL Chart, for students to think critically about where they currently are in their learning journey and where they want to go. The class should return to this chart after completing some of the activities listed below, to evaluate what they have learned and decide on next steps.

Sample of a KWHLAQ chart

It is important to encourage students to reflect on their learning as they investigate impacts of climate change through diverse perspectives. Ultimately, we want to consider how to integrate different points of view when considering solutions to the problem.

Note: In order to authentically integrate traditional Indigenous perspectives into the classroom, activities like a talking circle should become a part of your teaching practice and the origin and importance to Indigenous people should be explored. You should become familiar with circle protocols or courtesies for instance: no hierarchy, talking sticks, speaking in turn, no cross talk and respect for the speakerAdditionally, medicine wheels could be introduced as graphic organizers.

Sila Alangotok – Inuit Observations on Climate Change

Retrieved from: The Deepening Knowledge Project at The Ontario Institute for Studies in Education.

- This video explores the impacts of climate change on Banks island through an Inuvialuit perspective. The residents of Sachs Harbour have seen significant changes to their homes and have had to alter their way of life. For instance, foreign species of birds, insects and fish have invaded the land, ice is becoming dangerously thin, permafrost is melting which is moving the very foundations of this community, among many other changes.

- The Teacher’s Guide for the Video Sila Alangotok—Inuit Observations on Climate Change provides an extensive compilation of activities designed to extend learning, pose critical questions and support students in making connections after watching this video. There are nine separate activities included in the guide, each one able to stand alone. For the purpose of the current guide, we will highlight two excellent activities. You can access the downloaded version of the Teacher’s Guide in Teacher Aids.

Note: If students gravitate to an alternate video or story, from the provocations or otherwise, the framework for the following activities could be adapted to suit alternative resources.

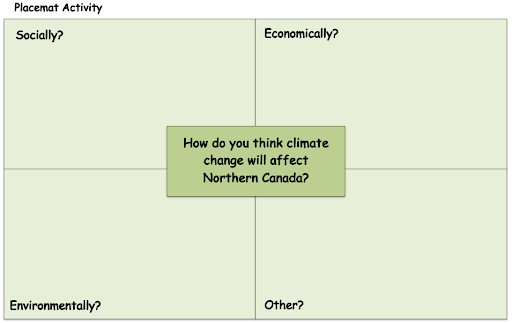

Activity 1: Placemat and Debate

Part A. Placemat

This activity will encourage students to make connections between key ideas and bigger themes explored in the video, guided by the question: “Based on your knowledge of the factors that contribute to climate, how do you think climate change will affect northern Canada?” Students are divided into groups to complete a placemat collectively. For more information on this strategy, click here.

Part B. U-Shaped Debate

After the placemats have consolidated some of the information in the video, the class will engage in a u-shaped debate to explore the statement: The observations of one community member complement and add to the understanding of climate change.

Students are invited to rebut and respond to one another’s arguments, and complete a reflection on the u-shaped debate in any format that seems appropriate to them: letter to action, persuasive essay, a video, a dramatic skit, etc.

Activity 2: The Impact of Climate Change on the Arctic (Adapted)

Part A. Compare and Contrast

There are many similarities between the observations that the Elders make, and predictions made by Western scientists. Students will use the higher order thinking strategy – Compare and Contrast – to deepen their understanding of these two different points of view. Encourage students to use a graphic organizer or chart of their choice to organize their thoughts. Click this here for more information on this strategy.

Part B. Conduct a Survey

Students will design a survey to compile observations about the effect climate change is having in their own community. It is worthwhile to take a bit of time to review your expectations for survey form and length, and to also explain how to write effective survey questions, including open-ended and closed-ended questions. (For tips on how to help students create an effective survey, click here)

Use the survey tools that students have created to find out about the impacts on local Indigenous communities as the community members observe them. Students have spent some time closely examining the effects that climate change is having on the Arctic and Inuit People, but not yet looking close to home. Foster existing connections with local communities or reach out to community members of your class or school that identify as Metis, Inuit or First Nations.

After obtaining the survey results from your local community, ask students to share: What did you learn that you didn’t expect?

Option 1: Return to Initial Questions

- One way for students to consolidate some of their learning would be to return to the initial questions provided at the beginning of this inquiry. These questions could initiate a small group discussion, written reflections, or a whole-class discussion and would be a good way for students to reflect on their learning process and synthesize some of the knowledge and skills that have been gathered throughout the inquiry.

- This could occur through simply writing down notes or doodling/sketching a creative visual that depicts the key information that students have learned throughout this inquiry.

Option 2: Rapid Feelings Check in:

- This activity involves a brief check in, asking students to think about their emotions and perspectives related to climate and the environment. Ask students to get into pairs, each person takes a turn speaking for one minute at a time. Some prompting questions to provide students are:

- How have you been feeling about the climate, activism, the environment and the future?

- How has your thinking shifted throughout this process?

- What realizations have you had during this inquiry?

- Has anything you’ve learned surprised you? Why?

Summarizing Learning with an Infographic

- Have students create a one-page infographic either individually or with a partner of the most important learning from this inquiry – It can be from the survey data they gathered, or other knowledge gained during this unit. For more information on infographics, click here.

Gallery Walk

- To add further engagement, the infographics should be shared with the rest of the class in some format, such as by conducting a gallery walk where the infographics are posted around the classroom and students rotate through them and are asked to write post-it-note comments on their observations or questions about other students’ work. For more information on gallery walks, click on the LINK.

- Story of the Salmon – W.D. Ferris – Richmond, BC (2013)

- Students developed and performed a play called the “Story of the Salmon” to highlight the connection between Richmond, BC, the Musqueam First Nations people and their traditional fishing and hunting territory, and the salmon migration. The students raised Coho salmon in the classroom and released them at the Little Campbell River Fish Hatchery. See their project here

- Canada’s North – A Balancing Act – David Livingstone Elementary School

- Vancouver BC (2016/2017) – Students wanted to feel a greater connection to their land, while searching for answers to the question: “What could sustainable northern development look like?” They set out to learn the history of our country from different perspectives and learn how Northern communities could thrive in the world that we’re living in today. Through an incredible, multi-dimensional field trip, they learned about nature, industry, culture and traditions in the Yukon. See their project here.

- United First Nation Youth Summit – Riverview High School Summit

- Riverview, NB (2019)- Fifteen First Nation communities across New Brunswick were invited to participate in the Youth Summit at Riverview school. Each community or school was asked to select 2-5 youth delegates, each selecting one of Education, Environment, Social Justice or Health & Wellness as a committee to participate in once they arrived. To prepare for participation in their respective committee discussions, delegates were asked to arrive ready to share/discuss a topic of interest or concern pertaining to their committee topic and relevant to their respective communities. See their project here.

- Walk for Water: A follow up from Strut for Shoal– Seven Oaks Met School – Winnipeg, MB (2019)

- When senior students at Seven Oaks Met School learned that the local community of Shoal Lake 40 First Nation (the very community where most of Winnipeg’s drinking water is sourced!) has been under a boil water advisory for over 20 years, they were inspired to take action. They used their passion for fashion and music to organize a benefit night at the local performing arts centre. They also organized speakers and elders, from both Winnipeg and Shoal Lake, to educate the audience about the water crisis. The event raised over $7,000 for the Shoal Lake 40 First Nation community and spread awareness across the region. Later that year, Seven Oaks students participated in the local Walk for Water event, which drew over 1,000 participants. The students gathered over 900 signatures for their petitions in support of clean water for all Indigenous communities across Canada. As a result of the students’ advocacy, Shoal Lake 40 First Nation will be getting a water treatment plant! See their project here.